May 14, 2023

By Layne Hartman and Tiffany Yang-Tran

Although human factors engineers strive to make usability testing as realistic as possible, FDA’s final guidance for training decay periods adds logistical complexity: 1) recruitment difficulties from the increased burden on participants’ time; 2) the increased cost required to compensate participants for extra; and 3) the extra time itself, which increases the length of the overall study. Some participants might also perceive the downtime as either wasted time, a missed opportunity to start an evaluation session earlier, or a chance to “study” what they have learned from their training session.

The Ebbinghaus Forgetting curve—which demonstrates that after 20 minutes, humans retain only 58% of what they just learned—underpins training decay studies within the human factors domain and models the decay theory currently employed in usability studies: forgetting occurs due to the passage of time. However, interference theory suggests forgetting is primarily due to other information that interferes with memory recall.

With retroactive interference, learning a second set of information disturbs our memory of a first set. This leads to a method that introduces a more practical decay period, reducing logistical complexities while maintaining representative, natural memory decay.

The studies described below highlight three cognitive factors involved in retroactive interference and how each factor impacts memory recall.

Material specificity addresses how the similarity of newly learned material affects recall of the originally learned material. Results from various studies suggest that the similarity or dissimilarity of materials is not paramount to the impact of retroactive interference. Other variables in the activity’s nature were also hypothesized to affect recall: the effects of verbal versus non-verbal interference, intentional memorization, and the introduction of new, meaningful information. Interestingly, there was no significant difference in recall performance between these various interference activity types. However, the presence of cognitive processing factors in an activity should impact the selection of an interference activity.

Mental exertion can be described by the amount of cognitive processing power required to complete a task. For instance, consider the mental demand of scrolling through social media versus completing a calculus problem set. Notably, mentally effortful tasks can include those with or without intentional memorization. Mental demand can be found in both a task that involves memorizing a list of words and a task that involves solving math problems. As such, a period of interference can be sufficiently mentally effortful, such that it leads to a reduction in recall performance.

Lastly, onset timing refers to the amount of delay after which the interference activity is administered. This factor considers whether the retroactive interference will have a greater impact on recall if it is introduced immediately after learning versus after a delay. A study showed that longer onset times resulted in better memory recall, theoretically because the originally learned and interference activity materials are more distinguishable.

Given that retroactive interference is critical in disrupting the encoding, storage, and recall of our memories, human factors professionals might be able to more accurately simulate training decay by employing retroactive interference. Moving forward, we need to consider the three factors of interference that impact memory recall to select the appropriate type of interference activity. We should ask ourselves:

-

What is an activity that is mentally effortful and considers material-specific interference?

-

When should we implement interference to appropriately simulate the natural decay users might experience after being trained to use a medical product?

We brainstormed several activities that incorporate the three factors noted above and that should be administered after the training session when interference might naturally occur. Notably, these activities have not been tested, and additional considerations should be made to avoid introducing negative transfer or test artifact. Interference activity suggestions include:

-

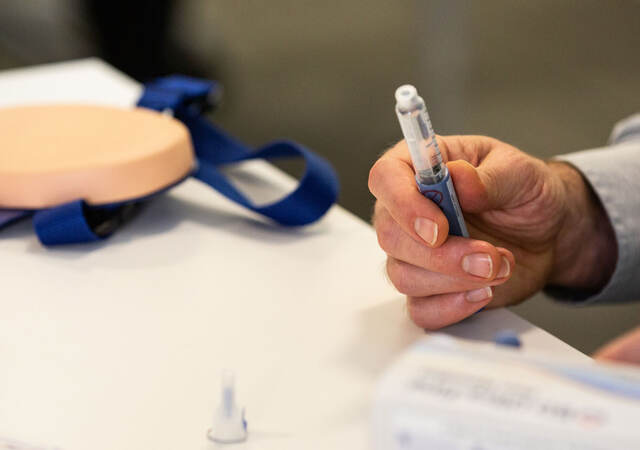

Learn about another type of medical product that treats the same condition (e.g., a diabetes management application to interfere with pen-injector training)

-

Present training on another, unrelated product and administer a short verbal quiz

-

Administer location and reading comprehension tasks for the instructions for use (IFU) of an unrelated product

-

Ask for subjective feedback on fictitious design elements (e.g., compare/rate fictitious IFU phrases or graphics, provide feedback on alternate color choices)

-

Conduct market research-related activities (e.g., card sorting, mind mapping)

Layne Hartman is Senior Human Factors Specialist and Tiffany Yang-Tran is Human Factors Specialist at Emergo by UL.

Request more information from our specialists

Thanks for your interest in our products and services. Let's collect some information so we can connect you with the right person.